It was 40 years ago--Thursday, May 28, 1959--a hot late spring

day in the Central California town of Fresno. I was 15, six years removed from

England and just 20 months from Canada. My late morning high school French class was

droning along when a message came commanding me to report immediately to Mr. Neal, the

vice-principal. I found Mr. Neal in earnest conversation with my father.

News had arrived just that morning via the immigrant grapevine on which all football

enthusiasts then depended in a strange land whose media never mentioned the football that is

played primarily with the foot. Word had it that England were to play the U.S.A. that very

night in Los Angeles, 250 miles to the south. No matter that the news was probably

25th-hand by the time it got to us. My dad was going on the chance it was accurate and,

God bless him, he had come to pull me out of school and take me along. As they say

nowadays, he had his priorities straight. This, he told Mr. Neal, was a once-in-a-lifetime

chance for me to see my homeland’s national team, and it was not to be missed.

Mr. Neal, in beneficent mood no doubt partly the product of my dad’s ability to

charm, said he’d make an exception for an event of such obvious importance to us and

allow me to go. My heart soared. As an afterthought, he asked, "You don’t

have any exams today, do you?" My heart sank. The consequences of fibbing about such

matters were known to me and compelled a truthful answer: I had one later that day. A

fateful pause, then he made the only humane decision. "Never mind," he declared,

"you’ll make it up." Hurrah! We were off.

Waiting in the car was Ludwig

Kuest, a 26-year-old German immigrant of

great heart and immense good cheer. Ludwig was the stalwart fullback on

the best of our local football teams, the club with which my father had just

ended, at age 39, a playing career whose potential World War II had consumed and which I

was to join a year later, after my father had become the coach. In a league

made up almost entirely of immigrant players, the team Ludwig captained was

named the Olympic Soccer Club because of its multi-national makeup--at one time

or another German,

Dutch, Scottish, Irish, English, Norwegian, Swedish, Czech, Hungarian, Greek, French,

Armenian, Peruvian and Mexican players. The club always had a single

U.S.A.-born player, at first a beefy fullback who had spent some time in Europe

and later a lanky youngster who lived near the park where we played, came to

watch the games and decided he wanted to be a goalkeeper.

Whatever differences may have divided

these immigrants when they lived in their native lands had been cast aside in

their adopted land, where they were firmly bonded together by their common

passion for football. Every Sunday afternoon during the season, a few

hundred faithfully gathered at a local recreation park for the week's matches. Many of us, whatever our nationality, went to German beer fests, Mexican

festivals featuring mariachi bands, Armenian wedding celebrations and the like.

And so our German friend Ludwig took the day off work to join us for our first big football match in the

U.S.A.

It was our first trip to Los Angeles, which didn’t have nearly as many freeways

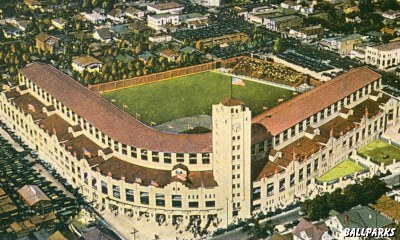

then. We didn’t have the vaguest idea how to get to the stadium, the

rundown Wrigley Field baseball park built by the chewing gum magnate in the mid-1920’s in

South Central Los Angeles, which had since become the ghetto that was to host the

celebrated Watts Rebellion in 1965. We didn't even know what time kickoff was.

It was rush hour when we reached L.A., Ludwig took over the wheel, and we hurtled down the bumpy

dirt strip on the side of the roadway at 50 and 60 miles per hour. "This is the way

they drive in L.A.," Ludwig proudly proclaimed as we whizzed by all the

other cars stuck in clogged traffic lanes. I could see my dad’s heart was

in his mouth, but he said nothing. Getting to the match in time was more important than

practically anything, and Ludwig seemed a good bet to do it.

After losing our way, which gave us the chance to marvel at "the Stack,"

several criss-crossing freeways set one on top another in downtown L.A., we found

Wrigley Field at last. Yes, the match was on, and we had half an hour to spare before

kickoff. We took turns predicting what the score would be. With a 15-year-old’s

confidence and without the slightest idea about the teams or their form, I guessed England

8, U.S.A. 1. In those days, our only way of getting results was through English

newspapers mailed by relatives still in "the Old Country," and they took six to eight weeks to

reach us. We did not

know England were finishing a disastrous tour of the Americas after three

straight losses to Brazil, 2-0,

Peru, 4-1, and Mexico, 2-1. There was no match program to bring us up to date.

It was a balmy evening. The crowd was slender, little more than 10,000, and the pitch,

too, was disappointing. Our seats were behind one of the goals, and in front and to

the right of that goal were the broad dirt paths of a baseball diamond.

The teams took the field, England in their usual white and black (no one will ever

convince me it was navy blue), and the U.S.A., if memory serves, in all dark blue. There

in the flesh were two men whose names I’d known since I was four or five. There was

England’s first manager, the splendidly named Walter Winterbottom.

And there was the

fabled England centre half and captain, the blond Billy Wright, accorded special reverence

in our family because he was born in the same house as my paternal grandmother in Ironbridge on the Welsh border. We did not know it then, but Billy was playing his last

international that night, his 105th, his 90th as England’s captain, his 70th

consecutive England match, all of these record numbers at the time. Indeed, it was his last

competitive match at any level; he retired from Wolverhampton Wanderers before the next

season began.

The rest of the England team included some names that now loom large in English

football history. At left wing for his 12th cap was Manchester United’s young star, Bobby Charlton,

who had survived the Munich air crash a little more than a year earlier, a tragedy that

had been the main front-page headline even in Fresno’s newspaper and that

had robbed the England team of three of its leading lights just before the 1958 World Cup--the reliable regular left back Roger Byrne, the high-scoring center

forward Tommy Taylor and the marvellous 21-year-old halfback Duncan Edwards,

whom many had reckoned would become England's greatest ever. I can still

remember the cry from my father, an Old Trafford regular in the late 1940’s and early

1950’s, when he unfolded that paper and learned nearly all United's

team had perished. Fate was incomparably kinder to Bobby, who went on to break Wright's appearance

record by one, finishing with 106 caps at the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. He remains

England's leading goalscorer with 49 and one of the few English footballing

figures to be knighted.

The

legendary Jimmy Greaves, then still with Chelsea, was making only his third

international appearance, at inside right. Jimmy didn’t score that night, but he

went on to break the England record of 30 goals jointly held by two other

England legends, Preston North End's Tom Finney and Bolton Wanderers' Nat

Lofthouse, and he ended his international career in 1967 with 44 goals in 57

games, a scoring total that only Charlton and Gary

Lineker (48 goals in 80 games from 1984 to 1992) have managed to surpass in many

more games.

At inside left for his 32nd cap was Johnny

Haynes of Fulham, whose defence-splitting passes had already earned him fame before we

emigrated from England six years before and who went on to captain England 22 times after

Wright’s retirement, ending his career with 56 appearances and 18 goals. West Bromwich Albion’s Don Howe, later on the England coaching

staff, was making his 20th of 23 appearances at right back. Blackpool’s Jimmy

Armfield, voted the best right back three years later at World Cup 1962 in Chile, was

earning his fourth of 43 caps, this time at left back. At right half for his 30th cap was

Blackburn Rovers’ Ronnie Clayton, who served briefly as England captain after

Wright’s retirement and finished with 35 appearances. Wolverhampton’s

immaculate Ron Flowers, making his 8th of 49 appearances, was at left half.

Things began badly for England and soon got worse. No doubt inspired by reminders of

their shocking 1-0 victory over England in Belo Horizonte, Brazil at the 1950 World Cup,

the

U.S.A. attacked furiously from the outset. England, facing the

goal with the dirt base paths in front of it, could do nothing right; their passes

repeatedly went awry and their shots flew wildly off the mark. After the

U.S.A. had a goal disallowed, they took the

lead at about 18 minutes through Scottish-born forward and captain Ed Murphy, delighting the

crowd, mostly immigrants from Continental Europe and Latin America who wanted to

see their adopted country upset the game's inventors once again.

At first we were numb with disbelief. This couldn't be. While

Hungary's celebrated 6-3 victory at Wembley's Empire Stadium in 1953 had brought to a crashing

end English claims to world footballing superiority--several years past the time they

had any basis in reality--the 1950 World Cup loss to the U.S.A. was still

regarded as a fluke. After all, England had beaten the U.S.A. handily, 6-3, in New

York City in 1953, a few months before the Hungary match. Yet the U.S.A.'s spirited

play and England's continued bumbling forced us to begin thinking another monumental upset might be in the making.

Ludwig maintained a diplomatic silence.

In that era, though, the U.S.A. national team hardly ever played, some years not at all. In

fact, it was only the 12th time a national side had been assembled since the

1950 World Cup nine

years before and the first time in almost two years. Murphy was a

U.S.A. regular for 15 years, from 1955 to 1969, but because the national team

played so rarely, he earned only 16 caps. Moreover, the U.S.A. players were drawn

from semi-professional clubs--many of them sponsored, strangely enough, by

funeral homes and automobile dealerships--which didn’t pay a living wage,

and that meant they were part-time footballers. They could hardly match their opponents' teamwork, skills and conditioning.

The inevitable--mystically elusive

in Belo Horizonte, where the U.S.A. were similarly overmatched--was not to be thwarted this time.

The U.S.A.'s attacking forays

became fewer and slower and their play more and more disjointed. England's

ball distribution became assured and smooth, and their superior

positional play began to take its toll. Gradually they took control of the

game, and only continued poor passing and finishing from the dirt base paths in

front of the U.S.A. net prevented several first half goals. England did manage

to equalize before half-time when Warren Bradley, Manchester United’s tiny

post-Munich outside right, nipped in through momentarily confused defenders to head home a long throw-in from Flowers, neatly

avoiding the difficulties the playing surface presented. It was Bradley's last

appearance for England although he scored twice in his three international matches.

The second half was, to put it charitably, a slaughter. At our end, goalkeeper Eddie

Hopkinson of Bolton Wanderers, making his 12th of 14 appearances, had nothing to do.

At the other, England now passed and shot from a grass surface, and they were

deadly. They put the U.S.A. goal under continual bombardment, and several long-range blasts

went in. Bobby Charlton scored three, including one from a penalty kick, Flowers two, and

Haynes and West Bromwich Albion's hefty center forward Derek Kevan one each. Kevan's was

his eighth and last international goal in the last but one of his 14 appearances for

England.

The final score was 8-1, just as I’d "predicted," and it appeared

England had taken it fairly easy once the match was out of reach. As luck--and the dirt

base paths--would have it, eight of the match’s nine goals were scored at the far end

from our seats, but the occasion and the result more than compensated for that.

My only disappointment was that it was over so quickly.

Home in Fresno about 4 a.m., I fell asleep to sweet memories of my first England game.

They had to last a long time. It was another 17 years before my next one

in 1976, when England met Brazil at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in the U.S. Bicentennial Tournament.

During the intervening years, England visited North America only once, in 1964 in

far off New York City, where they thrashed the U.S.A. 10-0 as Winterbottom's

successor, Alf

Ramsey, built and groomed the team that won the World Cup at Wembley a further two

years on.

Forty years after that grand evening at the long since demolished Wrigley

Field, my father, Harold Young, in his 80th year, has acquired a computer and follows

football on the web from his home near San Luis Obispo, California. No

longer do we depend on an immigrant grapevine rife with rumors and

uncertainties to learn of important footballing events in the U.S.A. The

North American media now report them. No longer do we wait weeks to get the football results and news from the

English newspapers. With the help of an eight-hour time

difference, we can read them on the web the evening before their publication

date. No longer do we wait decades for an England tour of the Americas to see

England play. We can follow England's fortunes in nearly every match by live

satellite telecasts, not the same as attending, of course, but immeasurably

better than two-month-old newspaper accounts.

There has been another big change in my football life.

Forty years on, I have a definite fondness for my adopted land's national team.

I must have seen them play 40 or 50 times in the Los Angeles area. They

have progressed from consistently hopeless performances against the stronger

teams to stunning victories over Mexico, England again, Colombia, Argentina,

Brazil and Germany. They have grown from a team of immigrant

part-timers to a team of native-born professionals. They have gone from

drawing a few thousand spectators, and sometimes only a few hundred, to playing

before crowds nearing 100,000 in the Coliseum and the Rose Bowl. They have

my support against any opponent but England.

Although I'm now much more American than English in every

respect, my support for England's team remains unchanged. I could no more

change that allegiance on the ground my home is the U.S.A. than a Chicago Cubs

fan could change his baseball loyalty to the Dodgers merely because he's

migrated to Los Angeles or a Manchester United faithful could become an Arsenal

fan simply because he's moved to London. In any event, it's been in my blood since I was four or five

years old, and I wouldn't change it even if I could. But that doesn't stop me

from cheering on the U.S.A. in all their matches save one or two a

decade.

That I still derive my greatest pleasure from

following football in general and the England team in particular more than 45 years after emigrating to lands at worst

hostile and at best indifferent to the rest of the world's game is a wonderful gift bestowed on me by my father.

And so I send my dad my deep gratitude, not just for taking me to my first England match, but, more important, for

all he did before and after that memorable night to pass on to me an

enduring love for our game.

Match Summary:

U.S.A. 1 England 8.

Wrigley Field, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A.

Attendance 10,000.