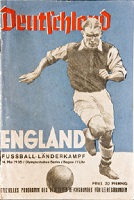

This

match is remembered as much for the England team's rending of the Nazi

salute during pre-game ceremonies in Berlin's packed Olympiastadion as it is for

the result, a thumping for the Nazi regime's sporting pride and joy.

It

was Germany's last match before

the World Cup

1938 Finals

in France in June, and they were full of confidence on the strength

of a 16-game unbeaten streak that had seen them go through 1937 with an

opening draw and then 10 straight wins, albeit that record was inflated by the level of the opposition they faced. Sepp Herberger had become

their second coach in September 1936, replacing Otto Nerz, and the only losses Germany had

incurred since he took charge came in his fourth and fifth matches in

October 1936, to Scotland in Glasgow 2-0, and to the

Irish

Free State in Dublin 5-2.

This

match is remembered as much for the England team's rending of the Nazi

salute during pre-game ceremonies in Berlin's packed Olympiastadion as it is for

the result, a thumping for the Nazi regime's sporting pride and joy.

It

was Germany's last match before

the World Cup

1938 Finals

in France in June, and they were full of confidence on the strength

of a 16-game unbeaten streak that had seen them go through 1937 with an

opening draw and then 10 straight wins, albeit that record was inflated by the level of the opposition they faced. Sepp Herberger had become

their second coach in September 1936, replacing Otto Nerz, and the only losses Germany had

incurred since he took charge came in his fourth and fifth matches in

October 1936, to Scotland in Glasgow 2-0, and to the

Irish

Free State in Dublin 5-2.

Germany

had become even stronger because the annexation of Austria in

the Anschluss of 15 March 1938, just two months before the meeting with

England,

gave them the pick of the many fine players who had performed for

Austria, perhaps Europe's strongest national side during the early 1930's

and still a tremendous force, although Germany had beaten the Austrian Wunderteam 3-2 in the third place match at the World Cup 1934

Finals in Italy. After the Anschluss led to

Austria's withdrawal from the

1938

World Cup Finals the month before this

match--Germany

notifying FIFA that Austria no longer existed--FIFA offered England

a bye into the competition, but

England rejected the invitation.

According

to Chris Nawrat and Steve Hutchings' The Sunday Times Illustrated History of

Football, England were determined that Germany should not benefit from the Anschluss in this

match and obtained an agreement that the German team would not include any

Austrian players on the condition that Aston Villa would play a friendly match

the next day against a combined German and Austrian team. Nonetheless, one of the players Germany lined up for this match, Hans Pesser,

who

scored Germany's third goal, had been an Austrian

international.

The

Nazi rulers regarded the match as a wonderful opportunity for political

propaganda, and the German team undertook preparations that were quite

extraordinary for the time, two weeks of intensive training in the Black

Forest. In contrast, per their usual practice then, the England team,

arriving just after the close of a typically exhausting league season, played

without any special training sessions. The English players were also far less

experienced in international play than their German counterparts. Only

captain Eddie Hapgood and Cliff Bastin had made more than 10 international

appearances. Two, left half Don Welsh and center forward Frank Broome,

were making their debuts, and inside right Jackie Robinson, who had made his

debut a year earlier in an 8-0 victory over Finland, was earning only his second

cap. Inexperience counted little on this day, however; Broome scored once

and Robinson twice.

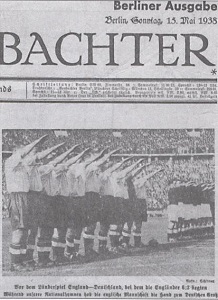

Before

the match, at the direction of the

British Ambassador to Germany,

Sir

Neville Henderson, and with the support

of Football Association Secretary Stanley Rous,

who would serve as FIFA President from 1961 to 1974, the England

players

joined in the Nazi raised-arm salute as the German

national anthem was played

and Nazi leaders Göring, Goebbels, Hess and von Ribbentrop watched.

Some accounts say the English players did so reluctantly, but others

maintain the fuss did not arise until the British press made it an

issue. In any event, England then set about dismantling a very good German team,

although sweltering

heat

eventually slowed them in the second half.

Left

winger Cliff Bastin, England's most experienced forward and

longest-serving player, opened the scoring with a well-placed volley at 16

minutes, but Germany pressed and equalized four minutes later through

inside right Rudi Gellesch. England then quickly took command of the

match. Germany needlessly gave away a corner from which Robinson

gave England the lead again at 26 minutes. Two minutes later Welsh

sent a defense-piercing pass through to fellow debutant Broome for

England's third goal. The fourth came a few minutes before half-time

from a wonderful solo effort by Stanley Matthews, who controlled a high

ball superbly, beat three German defenders and fired past the German

keeper. But as the half ended goalkeeper Vic Woodley's failure

to clear the ball properly allowed young German center forward Jupp

Gauchel to narrow the gap to two goals.

Early

in the second half, Robinson restored England's three-goal lead with a low

drive that veteran German goalkeeper Hans Jakob did not expect.

Broome missed a great chance for his second goal when he got by left back

Reinhold

Münzenberg, but sent his shot straight at Jakob. With less than 15 minutes left,

Pesser reduced the gap once again when he seized on confusion between

Woodley and right back Bert Sproston to score Germany's third. But

England were not to be denied their three-goal victory margin. With

10 minutes left, the little inside left Len Goulden struck a

tremendous shot from 30 yards that went in just under the crossbar

and tore the netting away from it.

The

result surely demoralized the German team. The next month in Paris, they

managed only an opening round 1-1 extra-time draw against Switzerland and went

out to the Swiss in the replay, 4-2. A little more than a year later

England and Germany were at war.

The career statistics of

the players who took the pitch that day demonstrate the toll World War II took on their

playing careers. England played no official internationals in the seven

years between May 24, 1939 and September 28, 1946. Of this England team,

only Stanley Matthews wore the England colours following the war, and he was

never again the international goalscorer he had been before the war. The

Germans continued playing internationals through 1942, but, expelled from FIFA immediately after the war in 1946, did not resume international play until

late1950. Of this German team, only Andeas Kupfer played internationally

after the war, and then

only once, in West Germany's single 1950 match.

The career statistics of

the players who took the pitch that day demonstrate the toll World War II took on their

playing careers. England played no official internationals in the seven

years between May 24, 1939 and September 28, 1946. Of this England team,

only Stanley Matthews wore the England colours following the war, and he was

never again the international goalscorer he had been before the war. The

Germans continued playing internationals through 1942, but, expelled from FIFA immediately after the war in 1946, did not resume international play until

late1950. Of this German team, only Andeas Kupfer played internationally

after the war, and then

only once, in West Germany's single 1950 match.

IN OTHER NEWS...

It was on 13 May 1938 that two convicted murderers were given

reprieves from their death sentences by the Home Secretary. 32-year-old

William Teasdale had strangled his wife, Ruby, in Clapham after she

confronted him with his new fiancée at a cinema, the night before.

27-year-old Stanley Martin had beaten a police constable, John Potter,

to death when he was disturbed after breaking into a cider factory at

which he worked, at Whimple, near Exeter. Both were commuted to life sentences, though it was

believed that Teasdale was released in the 1950s.